Eli Whitney’s armory was built along the Mill River for two reasons: water power and transportation. At the site, the low ridge of land that connects East Rock and Mill Rock created a natural waterfall in the Mill River, perfect for supplying power via a water wheel. Additionally, the Mill River was tidal up to the waterfall. Shallow-bottomed boats could travel from the Armory and through the river’s marshes below East Rock before joining the Quinnipiac River estuary and, only a few miles away, New Haven Harbor. This made it easy to transport supplies like iron and charcoal to the site and to distribute finished products.

Water: Power and Transportation

Before the introduction of steam engines in the early 1800s, work was completed by human or animal strength or with wind or water power. Water was the most consistent possible power supply and essential for operating any kind of heavy machinery.

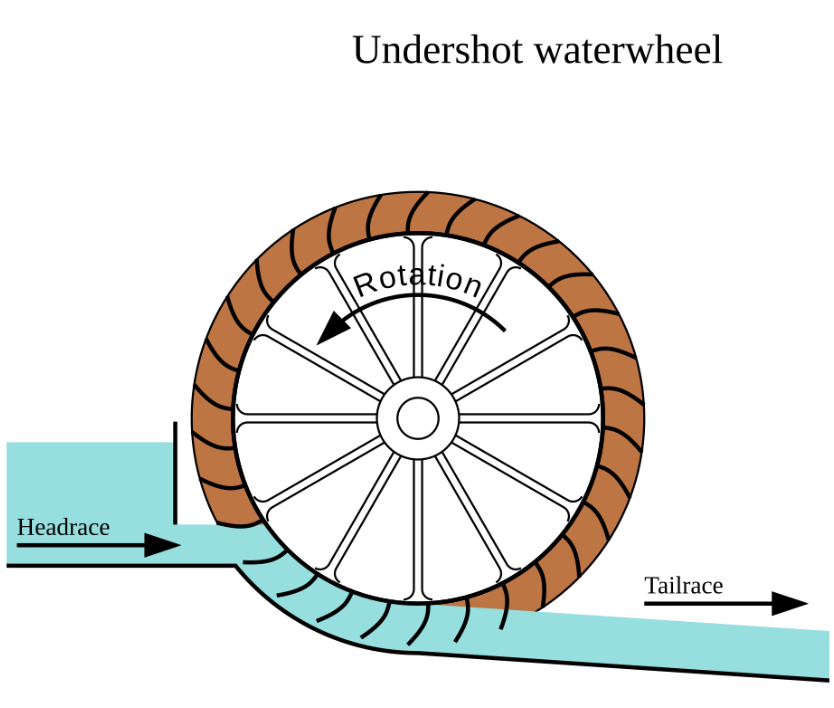

In water-powered mills, water would run past a wheel, pushing and turning Shafts connected to belts and pulleys that delivered power to machines. The belts and pulleys could be set up in many different ways. The first water wheels at the Armory were undershot wheels, powered by water running below them.

To supply the water to power the wheel, mills or factories were built where there was a reliable, powerful flow of water, like where a stream descended a slope. The Armory site is an example of this. Before the Lake Whitney Dam was built, there was a small natural waterfall where the Mill River meets the low ridge that connects the higher outcrops of East Rock and Mill Rock.

The Armory site was also perfect for transportation. The Mill River was tidal up to the waterfall. Shallow-bottomed boats could travel from the Armory and through the river’s marshes below East Rock before joining the Quinnipiac River estuary and, only a few miles away, New Haven Harbor. This made it easy to transport supplies like iron and charcoal to the site and to ship finished products to buyers.

Learn more: Geology and the Quarry

The Grist Mill

In 1640, the early New Haven colonist Sergeant William Fowler built a mill at the waterfall below East Rock. The river that powered the mill was named after it, as was the rocky outcrop that rose to its west: the Mill River and Mill Rock.

By 1665, Fowler’s mill had burned down - a frequent fate of mills, because flour is highly flammable. William Bradley and Christopher Todd rebuilt the mill. Todd and his family operated it for many years, leading it to be known as “Todd’s Mill.”

The millers improved the natural water power of the site by building a small dam across the waterfall, creating a millpond. From the pond, water could be released through a mill race, a small channel that directed at the waterwheel.

The mill was built to grind grains like corn or wheat into meal or flour. Grain intended for grinding is known as “grist”, and mills that produce flour are known as grist mills. The flour was needed to feed the new and growing New Haven Colony. Today, you can still see millstones at the Eli Whitney Museum and Workshop along the walkway between the Main Building and the Carter Studio. They are a record of the deep industrial history of the site.

[IMAGE: MILLSTONES?]

The mill below East Rock was the first of many mills and factories along the Mill River. It changed hands several times in the next 150 years. By the 1780s, it was owned by the Sabin family. In 1787, the Sabins sold it to James Hillhouse, Charles Channey, and Pierpont Edwards, business partners who were planning to build the Hartford and New Haven Turnpike through the property. These men in turn sold the mill site to Eli Whitney in 1798 for his new armory.

[LINK: Potential longer piece about water power???]

Crossing the River

The Whitney Armory site is divided in two by the Mill River. The main armory workshop buildings stood on the west bank of the river, where the EWMW’s workshop and exhibit buildings now stand. The east bank was the site of the forge and coal store and other auxiliary buildings. A simple, low wooden bridge linked the two sides of the river. It was supported by stone piers which survive and now support the replica of the Town Bridge. The original Town Bridge lay just north of the Armory where the Turnpike crossed the river.

[IMAGE] CAPTION: View looking east across the Mill River, 1906. The bridge linking the two sides of the Armory site is at center. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, HAER CONN, 5-HAM, 3-17.

[IMAGE] CAPTION: Photograph from around 1870, taken from the roof of one of the Armory workshop buildings, looking south along the Mill River with East Rock in the background. The Forge can be seen at left. The wooden bridge sits on stone piers that still exist. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, HAER CONN, 5-HAM, 3B-7.

Lake Whitney

In 1859, Eli Whitney Jr. started building a much larger dam at the Armory site, creating Lake Whitney. The dam and lake would solve two problems: the need for more water power at the Armory and the need for water in New Haven.

The dam was built with stone quarried from East Rock and Mill Rock. When completed, it was 38 feet high and 500 feet long.

The new lake stretched north for 2 miles. Three mills were submerged. 20 buildings were relocated to escape the water, as were three bridges, including the Town Bridge.

The original dam and reservoir have been expanded twice since 1862.

Water Power at the Armory

Water from the Mill River powered the machines in the Whitney Armory, including the main Armory building and the forge. An archaeological dig in the 1970s revealed the path of the forge tail race, which returned the water to the Mill River near the island.

However, as the Armory grew and its machinery became more complex, its original 6 foot high log dam, small millpond, and undershot waterwheels were not providing enough power. After he took over the Armory in the 1840s, Eli Whitney Jr. set out to solve this problem. In 1848, he introduced a more efficient vertical wheel contained in an iron housing. This type of wheel turned sideways, rather than up and down. It was far more compact - 4 feet in diameter, versus the 14 foot undershot wheel already used at the site - but much more efficient.

By the late 1850s, the Armory again needed more power. Lake Whitney would provide much more water to power new turbines.

The Armory and later occupants of the factory site continued to improve the turbine system as technology advanced. Water power was used at the site until 1933, when the last of the machinery was converted to electrical power. The final turbine building and the large metal pipe that fed it are still visible at the EWMW site.

New Haven Water Company

Like many cities, New Haven grew rapidly in the 1800s. In 1800, the population was around 4,000. In 1850, it was 20,000. In 1860, it was almost 40,000. The new residents were attracted by the city’s industrial boom, but the many new factories greatly increased the risk of fire. There was no city water supply, so fire prevention was difficult, and residents relied on wells to drink. Unfortunately, there was also no city sanitation system, meaning those wells were often unsafe.

The city needed a solution. In 1849, a group of New Haven civic leaders had founded the New Haven Water Company to create a city water system. They struggled to raise money and to overcome political opposition to their plans. In the late 1850s, Eli Whitney Jr. took over the company and began building the Lake Whitney Dam and the planned waterworks at the Armory site.

As well as the dam, the Water Company built water-powered pumps, a reservoir, and eighteen miles of pipe to carry water to New Haven. The system opened on January 1, 1862. The company provided water to private properties, fire hydrants, and public water fountains like the one built on New Haven Green. In 1871, the company introduced steam pumps to increase the efficiency of the waterworks. The pumps were housed in a pump house that still stands on Armory Street.

The NHWC grew with New Haven, acquiring other local water companies, building more reservoirs, and expanding the water system. In 1980, the company became part of the South Central Connecticut Regional Water Authority (RWA). Lake Whitney is still part of the RWA system and supplies part of New Haven’s water.

After a 1901 outbreak of typhoid fever, a waterborne disease, the NHWC built a water purification facility across Whitney Avenue from the Armory and Waterworks property. A purification plant still operates there today, and a new facility was built in 2005. It includes the distinctive shiny, steel-clad building that you can see from Whitney Avenue, Armory Street, and East Rock. Around the purification plant, the RWA built a public park that also embraces two historic buildings from Eli Whitney Sr.’s time: the boarding house [LINK] and the 1816 Barn [LINK], which is part of the EWMW.

Sources:

https://www.newhavenarts.org/arts-paper/articles/water-they-doing-in-th…;

https://www.rwater.com/about-us/storied-history/

http://www.waterworkshistory.us/CT/New_Haven/